In ancient times Aristotle viewed material (matter) as the starting point of the path on which the potential hidden in it is actualized and gets a form.[1] The projection of this idea on a human being brought Heidegger to the frightful idea that the maturity and completeness of a human is her/his death. A human (or “Dasein”), so long as it is, already is constantly its “not-yet,”[2] and therefore it is always “its end.”[3] A human being reveals herself/himself as Being-toward-death. However, so long as she/he is, the death is accessible to her/him just as an external event of others, not as an inner event accessible to reflection.[4]

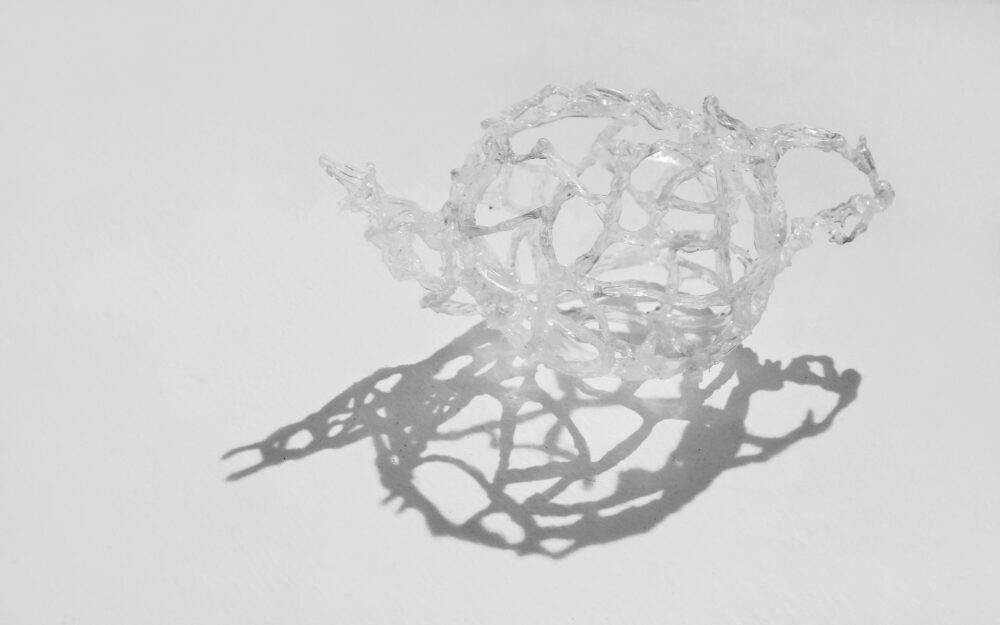

“Ontological Blood” is a rethinking and conjoining of Aristotle’s and Heidegger’s ideas. The series of objects is being created from broken glass vessels, subsequently glued together and cleaned of the original material — the glass. The original components of the glass reach their maturity through a human hand. Being-towards-death of mature things manifests itself through arrearance of cracks. The brokenness of glass and subsequent gluing together are just moments of maturation. Being-toward-death does not disappear without trace: the connection of the fragments leads, through a human hand, to the emergence of new forms that grow from their immanent potential for disappearance, which always was in these objects. At the same time, the crack-sculptures as a fixation of absence are not absence themselves: they stand out with what speaks about presence. They enable the voidness surrounding the sculpture to be seen as the path of the potential and the completeness of the form in its absence.

Resorting to everyday things, i.e. to what is ready-to-hand, is, as Heidegger said, a fundamental step in studying a human as Dasein, which is, in its own turn, a central element in investigation of the answer to the question about the meaning of Being[5]. In the deep past, these sculptures could be called “the soul of an object”; and fragility of glass could be seen as their skeleton or blood[6] solidifying after the death of a body. Could it be so that the ancient idea of blood lies underlines the main ontological question: what is the meaning of (Non-)Being?

References

| ↑1. | Arist. Met. 1032а19–22: “All things which are generated naturally or artificially have matter; for it is possible for each one of them both to be and not to be, and this possibility is the matter in each individual thing” (Aristotle 1933, 1989. Aristotle in 23 Volumes, Vols. 17, 18. Trans. by H. Tredennick. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; London: Heinemann). |

|---|---|

| ↑2. | Heidegger, M. (1962) Being and Time. Trans. from the German by J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson. Oxford: Blackwell. P. 288: “[…] as long as any Dasein is, it too is already its ‘not-yet’”. |

| ↑3. | Ibid. P. 289: “[…] just as Dasein is […] ‘not-yet’ constantly as long as it is, it is already its end too. The ‘ending’ which we have in view when we speak of death, does not signify Dasein’s Being-at-an-end [Zu-Ende-sein], but a Being-towards-the-end [Sein zum Ende] of this entity. Death is a way to be, which Dasein takes over as soon as it is”. |

| ↑4. | Ibid. P. 304: “Factically, Dasein maintains itself proximally and for the most part in an inauthentic Being-towards-death. How is the ontological possibility of an authentic Being-towards-death to be characterized ‘Objectively’, if, in the end, Dasein never comports itself authentically towards its end, or if, in accordance with its very meaning, this authentic Being must remain hidden from the Others?”. |

| ↑5. | Ibid. P. 231, 96: “What we are seeking is the answer to the question about the meaning of Being in general, and, prior to that, the possibility of working out in a radical manner this basic question of all ontology. But to lay bare the horizon within which something like Being in general becomes intelligible, is tantamount to clarifying the possibility of having any understanding of Being at all-an understanding which itself belongs to the constitution of the entity called Dasein”; “[…] which entities shall be taken as our preliminary theme and established as the pre-phenomenal basis for our study[?] One may answer: ‘Things’.” |

| ↑6. | Empedocles 31 B 105 Diels-Krantz (520 Bollack); The Fragments of Empedocles. Trans. by W.E. Leonard. Chicago, 1908. P. 49: “The heart is nourished, where prevails the power that man call thought; for lo the blood that stirs about the heart is man’s controlling thought”. Aristotle interpreted that passage as a description of the soul as blood: Arist. De an. А 2. 405b5. |